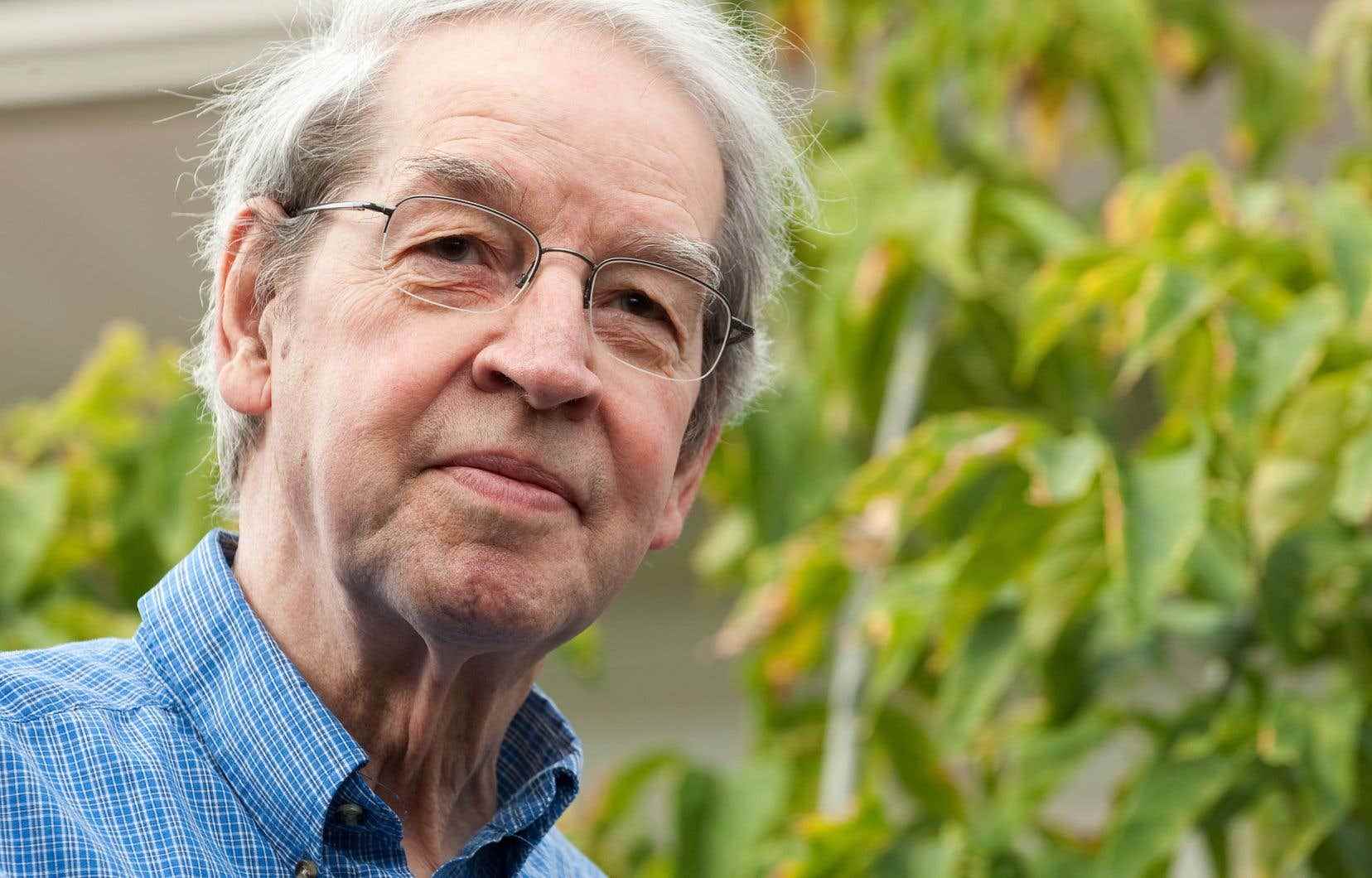

Jacques Brault, the poet of the intimate, the independent spirit, the giant in the shadows behind Gaston Miron or Saint-Denys Garneau, died last Tuesday following a long illness, at the age of 89.

Faithful to literature to the end, “enlightened marginal”, like the writer my colleague Christian Desmeules in 2005, he remained extremely discreet in the general public, while his work was celebrated in the literary world from the publication of his first collection, Memoryin 1965.

In 1996, when Jacques Brault was awarded the important Gilles Corbeil literary prize, literary critic Gilles Marcotte said that he read in him “all the questions that have crossed Quebec for more than a quarter of a century”, “but blindingly topical.

Because Jacques Brault has always fled the glare of the spotlight. His love of literature, he cultivated it day after day as one cultivates a garden, and shared it among others with his students at the University of Montreal, where he taught literature and medieval studies.

“When the time has come, by some adventure or other, lock me up in a cheap and unimportant book, And don’t forget my melancholic dragonfly wings”. It is through this quote from Jacques Brault that Frédérique Bernier, who wrote a book on the essayistic counterpart of the poet’s work, The essays of Jacques Brault, from thresholds to erasures, marked his disappearance on his Facebook page.

“It was part of his poetics to avoid big flights and to stay as close as possible to prose”, says Ms. Bernier in an interview,

“He is associated with names better known than his own, but he has always been discreet and withdrawn,” she says, adding that Jacques Brault would have convinced Gaston Miron to publish The Rape Manas he established the critical edition of the works of Saint-Denys-Garneau.

“He wrote a magnificent text on Gaston Miron which he helped to publicize”, specifies Ms. Bernier. “And a number of young poets were still working today in his wake”.

His own way

Combining poetry, essay and prose, Jacques Brault has paved his own way, unique and autonomous in the kingdom of letters. His first story, Memory, was part of the literature of the country, underlines Ms. Bernier. “His first great collection, Memory, is in line with the poetry of the country. But he traced his own voice, which is a darker path, from below, where he stays near the shadows, a voice much less flamboyant than that of Gaston Miron”.

Jacques Brault then distanced himself from the nationalist movement during the crisis of October 1970, denouncing the violence which then shook Quebec.

“When the events of October 1970 happened, he was shocked, says the poet’s daughter, Emmanuelle Brault, who signed a book on her father’s work in 2019, In the footsteps of Jacques Brault, Journey through the work of Jacques Brault. He was against violence. He was always a pacifist. Many then reproached him for this break with the nationalist movement. From that moment, she says, Jacques Brault no longer sees himself as a “politically engaged writer”. “He focused on poetry, which for him was more than a literary genre, it was a way of life”.

He traced this path alone, but revealed its secrets in his numerous collections.

In At the back of the garden, Jacques Brault thus celebrates intimate literature. “He erased the names of the authors, so that his book becomes like an enigma. It was quite characteristic of her way,” says Frédérique Bernier. For Jacques Bernier, she adds, “it is in the humility of ordinary speech that we finally find the universal and the anonymous”. “It is a work of both great humility and great humanity”.

Get to the point

This way of life was also the continuous attention to the infinitely simple, the infinitely small. As the years pass, Jacques Brault’s poetry becomes more minimalist.

“The more time went by, the shorter his poems became,” continues Emmanuelle Brault. They could line up, he didn’t mind. He really liked haikus. […] It is an evolution to seek the essential in less than nothing: a branch, a tree, a bird”. What we find at the end of the road.

In the novel Agony, which won him the Governor General’s Award in 1985, Jacques Brault explores the theme of death, as an old man leaves a notebook full of his writings on a park bench. A young man grabs it and takes the notebook home for the night. A unique way for poets to stay alive