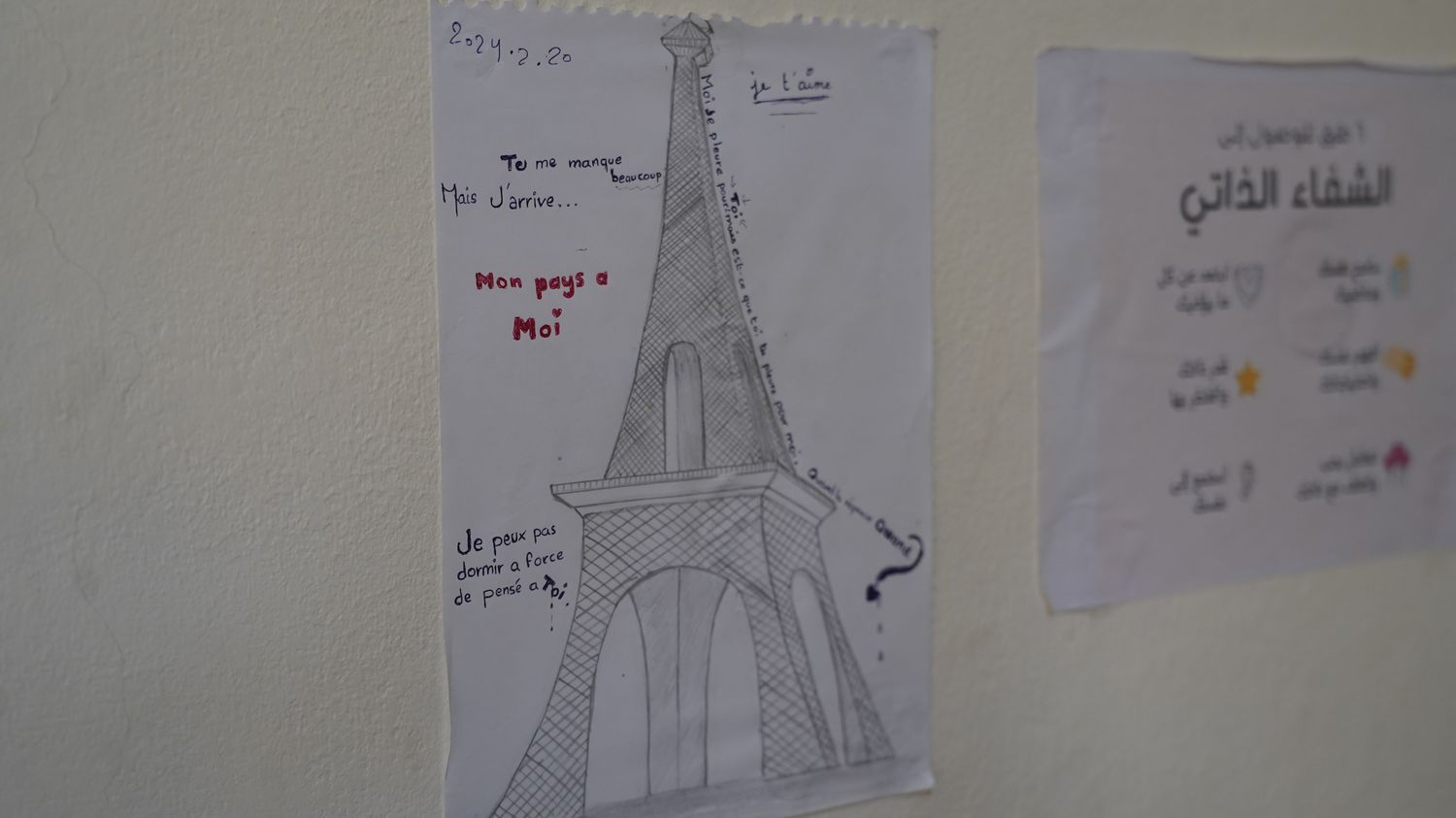

His drawing is plastered on the wall, just above his bed. In the center, the Eiffel Tower scribbled in pencil and this question in childish writing: “I cry for you. But you, do you cry for me?“Youssef, 19, has been dreaming of freedom for years. But behind the large iron doors of the Orkesh detention center, built along the road in the middle of the desert, the young Frenchman languishes in a cell for sixteen hours a day., like 147 other boys aged 12 to 21 locked up here. He can barely let off steam for an hour in the evening on the football field in the central courtyard before returning to his cell in 45 degree heat in this scorching summer.

Youssef was born in Strasbourg, he had already spent many years in prison before arriving at this rehabilitation center.It’s been about four years since they caught me in the camp, and they separated me from my family. When they see older children, they send them to prison.“, he says. His mother and his little brothers and sisters were repatriated to France, but not him: “I’m sick of all this, I’m sick of life. I don’t understand what’s going on, I want to find my family again“.

Especially since the young Strasbourg native was injured in Baghouz In 2019, during the fall of the Islamic State organization, he received shrapnel behind the skull and throughout his body. Today, his right hand is paralyzed, and his memory no longer works, he needs treatment, but on site the doctors cannot operate on him.I got hit by a plane, I can’t concentrate anymore“, explains the young man. After twenty minutes of conversation, he prefers to interrupt the interview.

Elias, too, is 19 years old, he was born in Bastia in Corsica, before moving to Le Mans, where he attended the École de la République and had birthday parties with friends.It was my father who brought us all here. My mother had nothing to do with it, she followed“, he said. Years later, he does not understand what he is still doing there, he too was separated from his mother and brothers and sisters, still detained in Roj, in a camp 3 hours away.

“Our morale, little by little, it weakens, it is like a battery, there is nothing to recharge it and little by little, it will turn off, regrets Elias. We have been waiting for years, our youth is leaving. Even if I have to go to prison in France, I don’t care, I want to get out of this nightmare and resume the course of a human life.“.

About a hundred kilometers aways From there, in another rehabilitation center, the Houri center, a sweet melody escapes from the establishment. For months, the young Asadullah, 18 years old, six of whom have been locked up here, has been practicing on a worn synthesizer, deep in‘A corridor. “Music helps me, my favorite is Frédéric Chopin“, confides the young man with sad eyes.

Asadullah grew up in Île-de-France, in Brétigny-sur-Orge, to a Chechen father and mother. A difficult and foggy childhood: “I remember my dad hitting me, I don’t have good childhood memories, my dad wouldn’t let me go out. I started skateboarding, but he didn’t like it“. In 2014, when he was in CE2, his father took him to Syria, with his two older brothers, far from his mother, and he died four years later in fighting in Raqqa. His brothers died shortly after. Asadullah was only 12 years old, he surrendered to the Kurds. Since then, he has lived locked up here.”The day will come when I will return to my countryhe confides. Every year I tell myself: this is the one. This is hope, a lie you repeat, to keep living“His mother is waiting for him in France with his little sisters whom he doesn’t know: “I want to see my life again“, implores the young Frenchman.

For the Kurdish forces that administer the northeastern region of Syria, these boys are potential time bombs. In the Roj camp, an open-air prison where 800 families of jihadists are held in tents in the middle of the desert, mostly women and their children, the boys are separated from their mothers as soon as they reach the age of 12.

Behind her tent, one of them, completely veiled, agrees to talk to us. This Algerian woman, detained here for four years, has an eight-year-old boy.I hope we’ll be gone by then, before my son grows up, because when your child is taken away, there’s nothing you can do.she assures. You haven’t heard anything anymore, it’s really frightening.“. The young woman protests: “Do they have the right to do this, to take them away from their mother?”

For Rachid Omar, the director of the Roj camp, they must be freed from the harmful influence of their mother. “Their own mother teaches them the ideology of the Islamic Statehe reports. On Fridays, they hold religious classes where they pray and have very extremist religious speeches and only talk about jihad.”

“These young people are training to become jihadists inside the camp.”

Rachid Omar, director of the Roj campto franceinfo

But for Rachid Omar, they are above all victims.Most of these children are sacrifices of the war. It is not their fault. But a solution must be found because, when they are over 18, the center can no longer keep them.“, he warns.

The next step for these boys is prison. A horizon that terrifies them. Recently, the NGO Amnesty International denounced the torture committed by the Kurdish authorities against jihadist prisoners.

In a building outside Hasakah Prison, which has more than 5 000 prisoners including 500 foreign jihadists, we were able, and this is rare, to meet a detained of Swiss nationality, arrested six years ago after joining the ranks of Daesh. Ayedin, 30, arrives in a green jumpsuit, his hands tied. The guards remove his hood. With a blank look, visibly malnourished, we are not allowed to talk about his conditions of detention, the interview is filmed by the Kurds, but he will tell us anyway, because no one else that we does not understand French in this room.”Everyone gets tortured“, assures Ayedin.

“They beat us with pipes, cables, batons… It’s the first time I’ve seen so many people die in prison.”

Ayedin, detained in Hassaké prisonto franceinfo

“It’s becoming a routine, reports Ayedin. It’s hard at first, but you have to get used to it. They put us in this prison to kill us slowly.”The prisoner says he is lucid: “I’m not surprised what they do to us. People think we get what we deserve, and I don’t complain to anyone. I accept it, I joined Daesh, what’s happening to me is normal“.

To the question: “would you like to be judged?“, Ayedin, a suspected terrorist, confides: “For me it’s like I’m being judged in fact, with everything they do to us it’s like I’ve made a judgment. Since 2019, time has stopped“.

The commander of the Kurdish Democratic Forces, Siamand Ali, denies any form of torture, these are only isolated cases for him. On the other hand, he assures that he needs much more means to succeed in subcontracting on his soil the detention of these thousands of families of jihadists who come from all over the world. The Kurdish intelligence services that we met assure that they have a file on each detainee to allow them to be judged. But it is impossible for the moment, in view of the regional instability and the threats from the Turkish neighbor to set up an international court to be able to judge them. Regarding the particular case of the children of jihadists, “it’s obvious“, assure the Kurds, “They must be repatriated, both for humanitarian and security reasons.“.

“There is no reason, in law, to refuse to allow a national who has French nationality to return to the territory. This is a very convenient benchmark, because we do not have any political questions or choices to make.“, analyses the former anti-terrorism judge David Benichou, who led the investigation into the attacks of November 13, 2015 in France.”The question that arises is the opportunity to support this return. Compared to the minors taken by force or born there, they have not committed any offence, they are not intended to be subject to legal proceedings other than through educational assistance, to ensure that they are removed from an environment that puts them in danger and that could turn them into a danger for our society.“, he pleads. For the magistrate, in a situation like this, “Fortunately, the law is a kind of reference point that is common to all of us, and if we fight terrorism with legal means, it is to apply the rule of law.“.